Listen:

Check out all episodes on the My Favorite Mistake main page.

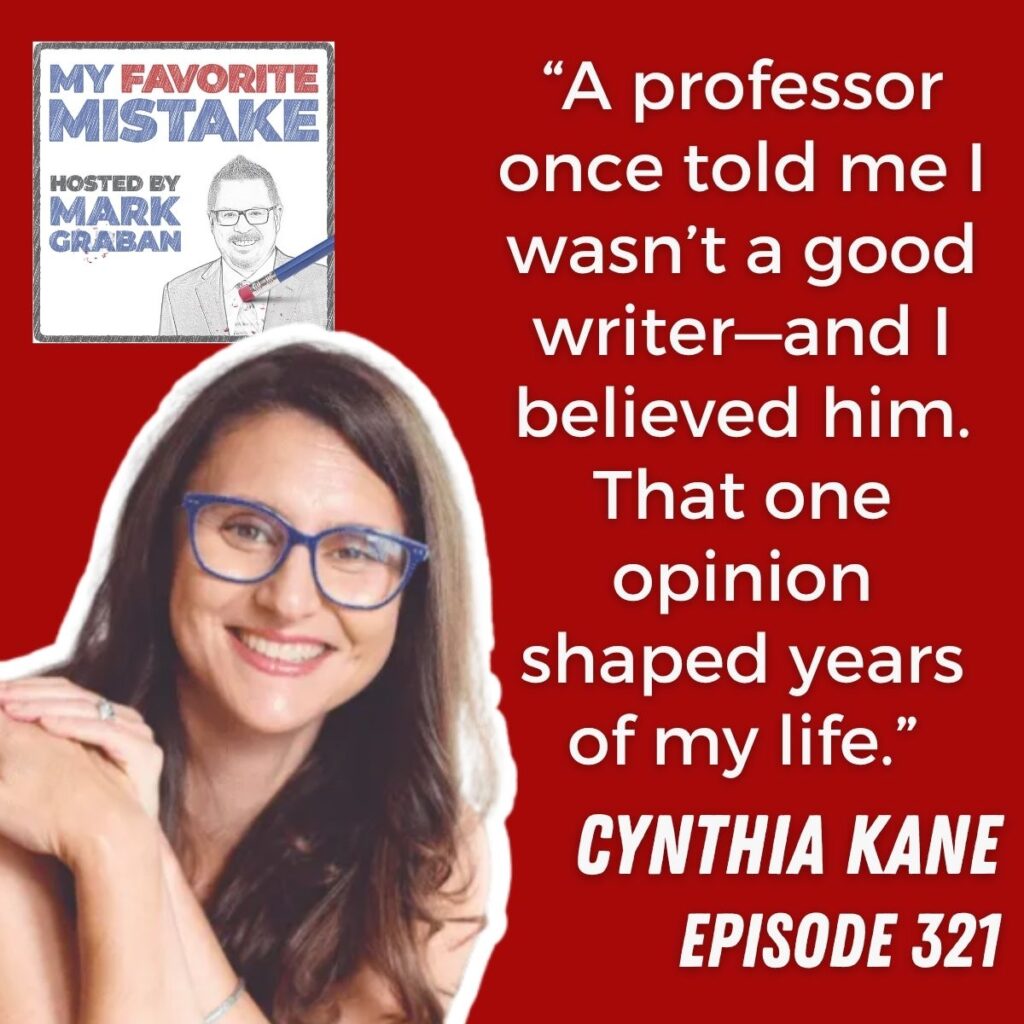

My guest for Episode #321 of the My Favorite Mistake podcast is Cynthia Kane, founder and CEO of the Kane Intentional Communication Institute and author of several books, including How to Communicate Like a Buddhist and The Pause: How to Keep Your Cool in Tough Situations.

Cynthia shares a pivotal mistake from early in her life: letting other people’s opinions matter more than her own—especially after a college professor told her she’d never be a good writer. That moment stung, but it also eventually propelled her toward a path of mindfulness, self-trust, and transformational communication.

Cynthia explains how her journey through loss, meditation, and Buddhist principles helped her develop a more intentional way of communicating—not just with others, but with herself. We explore how mistakes, reactivity, and emotional attachment can all be reframed through mindfulness and self-awareness. Cynthia offers practical tools for staying calm during high-stakes conversations, including pausing, resetting the nervous system, and learning to speak from an “empty place”—a state of clarity without judgment or reactivity.

“Every mistake leads us to something better.”

Throughout the conversation, we also unpack the difference between being nice and being kind, how communication impacts stress levels, and why helpful language is honest, kind, and necessary. Cynthia’s insights are especially valuable for leaders, teams, and anyone who wants to communicate more effectively under pressure. As she says, “Every mistake leads us to something better.”

Questions and Topics:

- What’s your favorite mistake?

- When did you realize that listening to others more than yourself had become a pattern?

- How did the loss of your first love influence your journey of self-awareness and healing?

- What led you to start writing again after being discouraged?

- What is creative nonfiction, and how does it differ from other forms of writing?

- Did working with an editor bring up old doubts, and how did you manage that feedback process?

- How does Buddhism shape your view on mistakes?

- Does that mindset help you approach writing mistakes differently?

- How do you balance detachment from mistakes with still caring about your work?

- What does “communicating like a Buddhist” mean in everyday life?

- Can you give examples where helpful vs. hurtful language is more subtle?

- What’s the difference between being nice and being kind?

- How does changing our communication style help reduce stress?

- What inspired your newest book, The Pause?

- What’s an example of a workplace situation where not pausing leads to regret?

- What should someone do if they need a pause but the other person won’t allow it?

- How can we calm ourselves in the moment to respond more intentionally?

- What does it mean to respond from an “empty place”?

- What breathing techniques do you recommend in tough conversations?

Scroll down to find:

- Video version of the episode

- How to subscribe

- Quotes

- Full transcript

Find Cynthia on social media:

Video of the Episode:

Quotes:

Click on an image for a larger view

Subscribe, Follow, Support, Rate, and Review!

Please follow, rate, and review via Apple Podcasts, Podchaser, or your favorite app—that helps others find this content, and you'll be sure to get future episodes as they are released.

Don't miss an episode! You can sign up to receive new episodes via email.

This podcast is part of the Lean Communicators network.

Other Ways to Subscribe or Follow — Apps & Email

Automated Transcript (May Contain Mistakes)

A Discussion with Cynthia Kane and Mark Graban

Mark: Hi. Welcome to My Favorite Mistake. I'm your host, Mark Graban. Our guest today is Cynthia Kane. She is the author of “The Pause: How to Keep Your Cool in Tough Situations.”

Cynthia helps people communicate more effectively in stressful moments, not just after them. She is the CEO of the Kane Intentional Communication Institute, and her previous books include “How to Communicate Like a Buddhist” and other books about Buddhism. So, Cynthia, thank you for being here. How are you?

Cynthia: I'm great. Thanks for having me.

Mark: There's a lot to explore, and I'm looking forward to a broader conversation about your books and experiences. But as we always do here, I'm going to hit you with the main question: What's your favorite mistake?

Cynthia: Okay, so my favorite mistake over the years has been listening to other people's opinions and thoughts more than my own. So many times throughout my life—when I was younger, growing into adulthood, into my career—everyone else's opinions were way more important than mine. I had a professor in college who was teaching classes while he was very ill. We would go to his house, and it was a poetry class. All I wanted to do was write. That was all I wanted to do when I was younger; I just wanted to write books.

I'll never forget, he told me after I got one paper back that had red ink all over it, and I went over to him and asked him, “What can I do? How can I make this better?” And he just flat out said, “You know, you're a nice girl, but you're not a good writer and you won't be one.” I mean, it was very harsh.

Mark: Ouch.

Cynthia: But that's an opinion. That's somebody else's thought, right?

Mark: Yeah.

Cynthia: I think for a long time that thought, that opinion, led a lot of my decisions. I stopped taking all literature classes. I started going into social sciences and things of that sort. But all of those thoughts that I listened to or opinions from others that I had listened to, while they led me down different paths than the ones I would choose on my own at that moment, they ended up bringing me to where I am now.

Cynthia: Right?

Mark: Yeah.

Cynthia: So all of those other people's voices made it so that I could really learn to listen to my own eventually.

Mark: And thank you for sharing that and reflecting on that. I'm curious, when did you recognize that to be a bit of a pattern? What prompted you to start listening more to your own thoughts?

Cynthia: Yeah, so I really found that in a roundabout way in the sense that I lost my first love very unexpectedly. When that happened, I was really forced into trying to figure out how to enjoy being here. Everyone tried to help and make life better for me at that time, and nothing worked. Everybody's opinions were there, everybody's thoughts were there.

I tried what other people were saying and thinking, and nothing worked. It was that moment of realization for me that was, “I have to figure this out on my own. This is something that I can't really rely on other people's opinions and thoughts for.” It's something I had to figure out for myself. So that's really when I started going to courses and retreats and reading books, and just trying to learn how to listen to myself.

That's when I was introduced to Buddhism and meditation and mindfulness. That's really when I started to listen to myself, and not only listen, but trust what I heard and would act on it.

Mark: And so one of the actions, I guess, was the first book. What was the first book? I'd be curious to hear what gave you the drive then to dive back into writing.

Cynthia: Yeah, so the first book was “How to Communicate Like a Buddhist.” What I had been figuring out from trying to enjoy my time here was that so much of it came down to communication. If I wanted to enjoy my environment or being with other people, it meant that I was going to have to learn how to communicate well with other people. If I wanted to communicate well with other people, I was first going to have to learn how to communicate well with myself.

I had taken a meditation and writing seminar at the Shambhala Institute when I lived in New York. That's where I learned meditation, and that's where I learned the elements of right speech in Buddhism, which is: to tell the truth, don't gossip, use helpful language, and don't exaggerate. When I learned all this and I learned how to meditate, I noticed that the way that I was relating to myself was changing. How I was talking to myself was changing. My relationships started changing as well. I used to be very passive-aggressive, very judgmental, had a lot of anxiety, had a very challenging time in silence, and being able to express myself.

All that started changing through using a different way of communicating, kind of this lifestyle experiment. So I started writing about it, and that's what “How to Communicate Like a Buddhist” became. I'd always loved writing, even though my freshman year poetry teacher had expressed his opinions and thoughts. It was something that I actually got back into after I took a semester off of writing and literature because I took one course over the summer to make up for credits from that class and I fell back in love with it.

I just continued to write and write and write. And so that's how I got back into it, really.

Mark: Yeah. I imagine someone's assessment of your attempts to write poetry is a different style of writing than nonfiction books.

Cynthia: Yeah.

Mark: Do you still write poetry, or did you shift into a different form of writing?

Cynthia: That's a good question. So I went from poetry to creative nonfiction. That was what I really started writing.

Mark: It sounds like an oxymoron. Sorry, what do you mean, “creative nonfiction”?

Cynthia: Creative nonfiction is pretty much any memoir you read. My books are creative nonfiction in that you're using story, but you're using elements of fiction to write nonfiction. So you use dialogue in nonfiction or you use an arc in a nonfiction book, those types of things.

Mark: Okay. And do you feel like even with that first book, did you have an editor working with you, or did you feel like you were hitting your stride and starting to believe that you were a good writer?

Cynthia: Yeah. I mean, it took me a long time to first believe that I had a publisher and a book deal for sure. But then with my editor, I think there was a lot of the first draft that I turned in and I got feedback on it. I went right back to that place that I had been before, where the other person's opinions and thoughts were more important than my own. And then I really had to work through that and think less of it being a put-down and a criticism and more, “How can I use this to improve my voice? Or how can I use this to improve what maybe isn't working?”

So I started taking another person's thoughts and opinions and thinking about them, and then choosing how I implemented them as opposed to it being like the Holy Grail.

Mark: I'd love to hear your thoughts on, and I've had other guests on the show who have talked about mistakes from a Buddhist perspective, how would you summarize or at least generalize the view on mistakes or this phrase, “mistakes are part of the path”?

Cynthia: They are. Yeah. I mean, I think that mistakes are a part of existing. We cannot live without making a mistake. And mistakes are how we learn and how we move forward. They really are there for us to be able to remind ourselves that everything is temporary, that everything is impermanent, and that this is a moment and now it's past, right?

So it really is a part of the rhythm of our day-to-day. Every mistake leads us to something better, I think.

Mark: It seems like you're prompting me to reflect as a writer, and the editing and refinement of the writing is such an important step. Does that Buddhist mindset help you? If you think of, “Oh, I made a quote-unquote writing mistake,” or, “Here's a sentence that wasn't clear, or here's a sentence that was a really awful run-on sentence.” Being able to move past that and make it better without dwelling on a mistake.

Cynthia: Yes, exactly. So there's a lot less dwelling on the mistake, or there's a lot less dwelling on what you didn't do well. Potentially, it's more around acknowledging that it's happened and then moving into the next phase, the next sentence, the next paragraph. So it's releasing a lot of judgment where there used to be more, right?

So it's noticing, “Am I evaluating myself in this moment? Am I judging myself in this moment? Am I attaching meaning to this mistake?” And if I am, can I drop the meaning? Just let it be a mistake. Just like you'd let a pen be a pen or oatmeal be oatmeal.

Mark: And letting it go. I'm curious about your thoughts on, it probably doesn't mean we don't care about the quality of our work if we're willing to let a mistake go. I'm curious about the balance between a healthy detachment that doesn't become like, “I don't care.”

Cynthia: Yeah. So a lot of people think that when we talk about detachment, it is that idea of, “I don't care,” but it's not that at all. It really is because you care that you release your grip. Because when we release our grip of something, then we can see it more clearly. So if I'm writing and I make a quote-unquote mistake, because I don't necessarily believe that there are mistakes, it's the…

Mark: Awkward part of having this conversation.

Cynthia: Yes, around Buddhist principles, but sure. It is strange. So it's the idea that if I were to make a mistake, then I am just going to step back and give myself space so that I can see it clearly, not judge it, morph it, change it, see if it needs to be different. And then because I am not emotionally connected to it, then it's easier for me to move to the next part, right? But the piece is like the attachment with Buddhism, attachment to our desires is often what brings suffering.

If I'm writing and I'm too attached to a paragraph or I'm too attached to a thought or an idea, it's going to drive me wild. I'm going to go mad, basically. I'm going to ask myself a lot of questions that I probably don't know the answers to. I'm just going to get myself worked up into a frenzy, and it's going to put me in a state of suffering. Suffering being discomfort, really. You know, it could be for a day, it could be for a month, I could be dwelling on something. But if we drop the attachment and we just see it as it is, that's more helpful than being attached. Does this make sense?

Mark: Yeah, yeah, it's very thought-provoking. And look, I've enjoyed the conversations with guests about Buddhism. I don't know that much about it. It's appealing. I'm not a student of Buddhism or a practicing Buddhist, but it seems like a lot that's helpful.

Cynthia: Yeah.

Mark: I want to go back a little bit to the title of your first book and the concept there of communicating like a Buddhist. I think a lot of the things you said there were very straightforward: be truthful, don't gossip. Using helpful language. I'd love to hear more about that and what that means to you, even in everyday life.

Cynthia: Yeah. So we have the opportunity within every interaction we have to use helpful language or hurtful language. So helpful language is language that moves a conversation forward. Helpful language is kind, honest, and necessary. Helpful language is specific. It is concise. The idea is that when we are expressing ourselves to someone, it should feel good for us, and it should feel good for the other person if it's additive. Hurtful language, on the other hand, takes away from the interaction. It creates more discomfort, it creates more doubt, worry, anxiety.

And it's not just for the other person, but for ourselves as well. So every moment, whether it's calling to order a cake for your son's birthday, or it's waiting on the phone for the tax people to finally pick up, or in the grocery store, at work, at home, we have the ability to pay attention to our language and ask ourselves, “Is what I'm about to say kind, honest, and helpful?” And if it is, then we want to continue. And if it is, then we take a moment, we can reset and begin again.

Mark: So can you think of an example? Maybe compare and contrast and an example where it's a little bit more subtle than obvious. We could all think of examples of things that are obviously hurtful instead of helpful. But are there interactions where the difference is maybe a finer line where people might get tripped up and be inadvertently harmful or hurtful?

Cynthia: So sometimes we can be kind, but we're not being helpful because we're not being honest, right? So in moments, let's say where you feel obligated to attend something, so you go and you're kind, but you're not genuinely coming from a place of wanting to be there.

Mark: So more of obligation?

Cynthia: It's more out of obligation. So your interactions are going to be more out of obligation than they are out of genuine want to be there. So you're going to suffer and feel uncomfortable, and then the other people that you're interacting with are going to feel that from you as well. So that's a more subtle way of it. Or if, you know, the classic example would be someone asks you, “What's wrong?” and you say, “Nothing.”

Mark: I mean, that might not be the honest right answer.

Cynthia: It's not honest. And because of that, you're feeling discomfort because you're not able to express yourself, and then the other person is uncomfortable because they can tell that something's wrong, but they're not sharing information.

Mark: Right. And, you know, one thing I think of a good friend of mine that was an early guest here, Karen Ross, who wrote a book called “The Kind Leader,” has helped in differentiating between kind and nice. I'd be curious to hear your thoughts because I think, kind of summarizing what I've learned from her, is that nice might be focused on not wanting the other person to feel bad, or kind is meant to be more helpful.

Cynthia: Yes. Yes.

Mark: I'd love to hear your thoughts on that distinction. And is it better in most cases to be trying to be kind instead of being nice?

Cynthia: I think nice is, it kind of falls into a bit of what we were just talking about. Being nice is not necessarily genuine. We can be nice to people without liking people. We can be nice to people without really being helpful. We can be nice to people and still judge people. Whereas with kindness, kindness is an embodied practice. We cultivate kindness. Nice is almost like a sticker, if that makes sense. Kindness is more of a practice that we feel in our body. So we cultivate kindness and we become kind.

Mark: Is that part of, and one thing you write about is the connection where changing your communication style can reduce your stress levels. I think you talked about reducing anxiety earlier. Is that because if you recognize that you're not being honest, that that internal stress can build up? How would you describe that?

Cynthia: So it's, when we're interacting, we can't rule out our nervous system or what's going on within us. So oftentimes when we're communicating and there's maybe a heated interaction or it's a difficult interaction, our body is in a heightened state. And so there's cortisol running through our body, the stress hormone. Because of that, our language can be impacted. We become more impatient. We can be nice, meaning we're kind of passive-aggressive nice, you know, we can lash out, we can shut down.

And so the work is to see, in communicating, can we move ourselves into feeling more of that rest and digest part of our nervous system to that safe place within our nervous system so that we're more calm, so that we can access that kindness? We can access that want to be helpful to somebody else in a genuine way. Whereas when we are caught in the fight, flight, freeze, we can't access ourselves. And so that's when we come off as different than how we respect ourselves sometimes.

Mark: So I'd like to talk, Cynthia, about your new book, and the first one that gets out of the pattern of previous books of, “How to fill in the blank like a Buddhist”—“How to Talk to Yourself Like a Buddhist,” “How to Communicate Like a Buddhist,” “How to Meditate Like a Buddhist.” The new book is “The Pause Principle: How to Keep Your Cool in Tough Situations.” I'm always curious to ask an author what was the story behind this book and how it came to be, what inspired you to write on that topic?

Cynthia: Yeah. So with a lot of the work that I do, teaching around how to change the way that you communicate, what was coming up a lot for people and also, you know, personally, is when you get into these difficult, heated, high-stakes conversations, challenging moments, what do I do in the moment? If I can't sit and think about, “Okay, I'm going to have a difficult conversation, and so these are the things that I want to address in this conversation,” if I don't have the opportunity to do that and I'm in it, how in the world can I show up in a way that I respect? How do I stay calm in a conversation that has me wanting to run away or completely shut down, right? And so that was the question that kept coming up more and more and working with people more and more around how to do that.

So how to create that moment, that space between the stimulus and the response, increase our capacity for discomfort so that then we can stay in the conversation, stay in the room. So it really came out of the need that I was seeing not only in my own life but in the lives of those that I was working with. And what was happening more and more was seeing a lot of companies paying for their employees to take my training program. A lot of the want was for this specific moment to be able to handle confrontation, to be able to handle conflict, and to be able to navigate it without shying away or not being able to have the hard conversations that need to be had.

Mark: So what's an example, maybe a workplace scenario, of somebody being in a situation where they didn't pause? And that leads to something maybe everybody wishes hadn't happened. And there are probably examples of people getting upset, people getting provoked, and letting emotions show.

Cynthia: Yeah. And I mean, it can really ruin team dynamics. It can create a loss of trust. And it also doesn't create an environment that people want to show up for. And so loyalty kind of goes out the window. And there's a lot that breaks down when reactions are high, for sure.

Mark: There are probably different dynamics, let's say, thinking in workplace scenarios where formal positional power comes into play. When you talk about losing trust and the things you're talking about there, I'm thinking of a scenario where a leader doesn't pause and gets upset at something an employee said.

Cynthia: Yeah.

Mark: It could also happen, I guess. I mean, I've been guilty of, I think of a recent situation, and I got some coaching or discussion about a similar idea. Instead of reacting in the moment, I got upset about something that I thought was a bad decision that was flowing upward, and it didn't go well, wasn't well received. It distracted from the issue. I got some feedback like, “Well, you shouldn't have gotten upset about that,” which I thought was unfair.

Cynthia: Yeah.

Mark: Unfair feedback.

Cynthia: I'm like, “Unfair feedback.”

Mark: “Don't do the upsetting thing.”

Cynthia: Yeah.

Mark: And we eventually worked through to where that decision got changed because of the feedback that I gave. But it was a really bumpy, if not a little bit damaging, experience to go through. I didn't pause.

Cynthia: Yeah. Yeah. And I mean, I think that most of us don't pause. It's not something that anyone has ever taught us how to do. And it is something that, in hindsight, when we look back on many moments, it would have been helpful to do. Right?

Mark: Yeah, because I mean, I think the bit of feedback, you know, kind of third-party coaching, and I'm curious to hear your reaction to this, was, in that moment, what I could have done was to say something like, “Well, I'm very surprised to hear this decision and I need some time to process that. Is it okay if we pause?” Like, literally, “Can we get back together later today to continue the discussion?” I did not have that in my repertoire of things to do. I kind of went into attack mode. “Well, let me tell you why I disagree and let me tell you why I think this is wrong.” I'm not a prosecutor, but I think I went into that “I'm going to prove my case” sort of mode.

Cynthia: Yeah.

Mark: I mean, is that a realistic thing to say, “Well, hey, you know, let's pick this back up later”?

Cynthia: It is a realistic thing to say, though. You have to be able to get to the place to be able to say it, right? It's not something that you would just be able to say without acknowledging and having an awareness that there is discomfort in your body. In that moment when the other person is telling you what their thoughts are or what their decision is, there's something going on in your body right away that tells you, “Okay, this is uncomfortable for me.” Whether it's like your heart starts beating faster, you start feeling like you want to vomit, your jaw gets clenched and tight, your hands maybe turn into fists without even knowing it, right? There's something sensationally that happens within all of us in this uncomfortable moment. So first you have to actually know, “This is uncomfortable for me. I don't like what this person is saying.”

Then, when you know, “Okay, I don't like this, I can feel this discomfort,” that's your cue to bring in a practice to help yourself feel safe. Because like you said, right in that moment, you're feeling attacked, so you just want to pounce back. That's human. That's human nature. That's how we're wired.

Mark: I shouldn't beat myself up for reacting that way. It's a very natural human reaction.

Cynthia: 100%. It is human reaction. We are wired to react. We are also wired to connect. But to be able to connect, we have to interrupt the pattern. So really, in that moment, you feel the discomfort. That discomfort is your cue to know, “Okay, I'm going to react in the way that I usually do, but instead, I'm going to break this pattern. I'm going to pull in a practice.” Maybe I'm going to start tapping my fingers. So I'm going to put my pointer to my thumb, my middle to my thumb, my ring to my thumb, my pinky to my thumb. And I'm just going to say, “You know, I can be calm right now. I'm feeling really upset right now.” You're breaking up the feeling of being attacked, basically.

Mark: And if you're on a Zoom or Teams call, like I was in this one situation, nobody sees that you're doing that.

Cynthia: No, nobody sees it. So you're just working through the challenge that's happening within you, and you're telling yourself in the moment, “Everything's fine. Calm begins with me. I can handle this conversation. I can calm myself down right now.” And you're tapping and you're listening and you're tapping. That type of thing. There are many practices you could do. But the idea is that you want to pull in a practice to help calm the nervous system, to calm the body so that it feels safe, so that then you can look at him and you can say, “You know, I really need a bit more time to digest what you're saying. Let's pause this and come back tomorrow.” You can't get there until you've let your body and mind know that it's safe and that you can express yourself.

Mark: Yeah. I think I've gotten better at recognizing when I'm sort of in that activated or some people might say, triggered, sort of state of how that feels because I've made the mistake many times of firing back an email response while in that state. One thing I've recognized is, “Okay, that doesn't work out well.”

Cynthia: Right.

Mark: So maybe I write the email that I want to write in a Word document and then delete it and get into a better place where I can be more helpful.

Cynthia: Exactly. Yeah. Where your language can be more helpful. So, I often tell people, “Your initial reaction will be the same. You're just going to change your relationship to that reaction.” But, you know, let's say through email, you get something, you don't like it. You can have that initial reaction on a Word document or on a piece of paper with a pen right next to you and just get it out. Then the emotion isn't there. You're not attached to it anymore. So then you can look at it clearly and you can respond from an empty place.

Mark: When you say, “an empty place,” that's an interesting phrase. Can you say a little more about that?

Cynthia: So you're not, there's no more charge within you, right? And there's no more judgment. There's no more evaluation. All that's left is clarity. Once we remove the emotion, we can see clearly. So we can see from an empty place, meaning there's nothing that's clouding our judgment. We're just seeing what is real or that needs to be responded to.

Mark: Right. I'm sorry, I'm thinking back to that interaction. I might have told the story in another episode. My one attempt in that moment to take a pause was to take a breath.

Cynthia: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Mark: The problem was, because it was in a one-on-one virtual meeting interaction, do you know how that breath ended up sounding? I can imagine because I looked off into the distance, and my attempt at a breath sounded more like… forgive me for the…

Cynthia: Yeah.

Mark: Is that kind of what you were expecting?

Cynthia: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. So the thing with breathing in those moments is often we forget to breathe. So when something like that happens and we say, “Okay, just take a breath,” it's going to potentially sound like that because we're actually holding our breath a lot of the time.

Mark: And then I let it out.

Cynthia: Yeah, and then you let it out. So it comes out kind of like as a sigh and like a… kind of thing.

Mark: Yeah, it sounded upset.

Cynthia: Yes. So one thing you can do is to do more like a breath pattern instead of just a breath. So meaning you would inhale for five, hold for five, and then exhale for five.

Mark: Let it out slowly.

Cynthia: Yeah, yeah. So it's more intentional with the breathing as opposed to it being, “I'm going to take a breath,” but I'm not really going to pay attention to the breath that I'm taking. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Mark: It comes back for you.

Cynthia: In that, though, that.

Mark: Well, thank you. And I mean it comes back to things that can be difficult: being mindful, being present, being intentional.

Cynthia: Yeah. I mean, it is. It's an active practice, right? Which makes it challenging because we like to do the easy thing, which is the unconscious.

Mark: What would be your strategy or recommendation if you suggest the type of pause that says, “Let's come back to this later,” and the person you're interacting with kind of refuses the pause or says, “Well, I don't have time. We have to address it now”? If they're not willing or able to give you time to calm down, what would your, I mean, what's the best we can do in a situation like that?

Cynthia: So what I would say is, I would say, “Okay, so then what I need, I just need about five minutes where I can, I'm just going to close my eyes and I'm just going to think, and then I'll be able to get back to you.” So you use the time in the room, but you're creating the boundary in the space you need to be able to get to clarity. So most of the time we can get to clarity pretty easily if we close our eyes. So often it really is just saying, “I need a couple minutes to process this on my own. I'm just going to close my eyes for a few minutes so that I can think about it.” And then in those few minutes, you're closing your eyes and you're asking yourself the question so that you can hear the answer.

Mark: And hopefully the person or people you're interacting with can be kind enough and empathetic enough to allow that to happen. And if not, that might lead someone to question things at a bigger picture.

Cynthia: Exactly. So that then leads to another discussion, another conversation that would need to be had, right?

Mark: Yeah.

Cynthia: You know, it could even be, “I really want to give the best decision that I can in this moment. And so what would be really helpful for me is if you give me the space to do that in this room.”

Mark: So then you're not framing it just in terms of what I need, which I think can be fair and valid and necessary, but also then, “Well, here's what the benefit of this will be.”

Cynthia: Yes. It's saying, “You know, I want us to get to the best decision possible. For that to happen and for me to give you the best input that I can, I need these five minutes at least to just sit and think through this.”

Mark: Well, hopefully there's been nothing in the conversation here today that would have made you want or need a pause. I think it's been…

Cynthia: I've loved it.

Mark: I think it's been a great conversation. I think it's really fascinating. And I appreciate you sharing your story and how you evolved. And I'm glad that you were able to rekindle that passion around writing and to turn it into so many books that I'm sure are helping a lot of people. I'm sure that feels good.

Cynthia: It does. It feels great. Yeah.

Mark: So again, our guest today has been Cynthia Kane. Look for links in the show notes to her website, to her books, and everything that she does. So again, that most recent book is “The Pause: How to Keep Your Cool in Tough Situations.” Thank you so much. Thanks again, Cynthia, for being a guest.

Cynthia: Thank you.